Edit Current Bio

UCB is written collaboratively by you

and our community of volunteers. Please edit and add contents by clicking

on the add and edit links to the right of the content

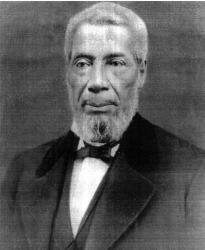

Samuel Davis

Born on 8-13-1810. He was born in Temple Mills, ME. He is accomplished in the area of Community.

- Basic Info

- Relations

- Organizations

- Accomplishments

- Schools

- Employers

Samuel Davis was born on August 13, 1810, in Temple Mills, Maine. He moved to Buffalo from Windsor, Ontario sometime in the late 1830s and quickly became a respected community leader. A learned man, Davis had attended Oberlin College. Although there's no information that he received a degree, the 1836 Oberlin Catalogue lists Samuel Davis as a registrant in the Collegiate Department. A mason, by trade, Davis was also a minister. In 1842, he was called to pastor the Michigan Street Baptist Church, the second oldest African American congregation in Buffalo. The church history credits him with helping to construct the church's new building - still a house of worship - on Michigan Street in 1844.

Samuel Davis was hired as a principal teacher for the Vine Street African School in 1842. A Davis descendant has written a comprehensive biography of his ancestor and published a copy of the contract that Davis signed with the City. It dates his final appointment at the Vine Street African School from July 1845 to June 1846. However, it appears that Davis vacillated between working for the City and his own entrepreneurial educational endeavor.

Davis was paid an annual salary of $300. While this may seem to be a fair wage for the era, White reports that Black teachers were discriminated against by being paid lower wages. White also notes that white teachers at Vine Street were paid less than their counterparts in the District schools. Many parents complained that the salary discrepancy resulted in the school having some unqualified and incompetent teachers.

Davis' tenure in the African School ended when he left and started his own private school for Black students, probably in 1844. The English-Colored School was housed at the Vine Street African Methodist Episcopal Church. Co-incidentally, the Vine Street African School was located across the street from the church. McGruder Chase noted that the city had about one hundred African American children eligible for school enrollment at the time. Davis recruited a quarter of those students to attend his school. The quality of the education appears not to have been an issue. However, their parents were not able to pay the tuition to sustain the school, and Davis was forced to close his school. According to Richardson, Davis returned to the Vine Street African school for the contracted year, 1845-1846, and left Buffalo the following year.

Davis was an accomplished orator and a vocal and active member of the anti-slavery movement. In 1843, he was the chairman of the National Convention of Colored Citizens held in Buffalo. He delivered a powerful keynote address in which he laid out the demands of African Americans. His position as a leader in this historic convention and his remarks offer some insight into the character of this pioneer. He was unapologetic in both his demands for equality and his call for African Americans to take responsibility for acting to achieve their goals.

"I will simply say, however, that we wish to secure for ourselves, in common with other citizens, the privilege of seeking our own happiness in any part of the country we may choose, which right is now unjustly and, we believe, unconstitutionally denied us in a part of this Union. We wish also to secure the elective franchise in those states where it is denied us, where our rights are legislated away, and our voice neither heard nor regarded. We also wish to secure, for our children especially, the benefits of education, which in several States are entirely denied us, and in others are enjoyed only in name. These, and many other things, of which we justly complain, bear most heavily upon us as a people; and it is our right and our duty to seek for redress, in that way which will be most likely to secure the desired end."

Samuel Davis was hired as a principal teacher for the Vine Street African School in 1842. A Davis descendant has written a comprehensive biography of his ancestor and published a copy of the contract that Davis signed with the City. It dates his final appointment at the Vine Street African School from July 1845 to June 1846. However, it appears that Davis vacillated between working for the City and his own entrepreneurial educational endeavor.

Davis was paid an annual salary of $300. While this may seem to be a fair wage for the era, White reports that Black teachers were discriminated against by being paid lower wages. White also notes that white teachers at Vine Street were paid less than their counterparts in the District schools. Many parents complained that the salary discrepancy resulted in the school having some unqualified and incompetent teachers.

Davis' tenure in the African School ended when he left and started his own private school for Black students, probably in 1844. The English-Colored School was housed at the Vine Street African Methodist Episcopal Church. Co-incidentally, the Vine Street African School was located across the street from the church. McGruder Chase noted that the city had about one hundred African American children eligible for school enrollment at the time. Davis recruited a quarter of those students to attend his school. The quality of the education appears not to have been an issue. However, their parents were not able to pay the tuition to sustain the school, and Davis was forced to close his school. According to Richardson, Davis returned to the Vine Street African school for the contracted year, 1845-1846, and left Buffalo the following year.

Davis was an accomplished orator and a vocal and active member of the anti-slavery movement. In 1843, he was the chairman of the National Convention of Colored Citizens held in Buffalo. He delivered a powerful keynote address in which he laid out the demands of African Americans. His position as a leader in this historic convention and his remarks offer some insight into the character of this pioneer. He was unapologetic in both his demands for equality and his call for African Americans to take responsibility for acting to achieve their goals.

"I will simply say, however, that we wish to secure for ourselves, in common with other citizens, the privilege of seeking our own happiness in any part of the country we may choose, which right is now unjustly and, we believe, unconstitutionally denied us in a part of this Union. We wish also to secure the elective franchise in those states where it is denied us, where our rights are legislated away, and our voice neither heard nor regarded. We also wish to secure, for our children especially, the benefits of education, which in several States are entirely denied us, and in others are enjoyed only in name. These, and many other things, of which we justly complain, bear most heavily upon us as a people; and it is our right and our duty to seek for redress, in that way which will be most likely to secure the desired end."